Climber and photographer Cory Richards’s most famous photo was the result of an event that nearly ended in tragedy. In 2011, he was caught in an avalanche while descending from the first successful winter summit of 26,362-foot Gasherbrum II. He took a self-portrait of his distraught face, framed by goggles and a snow-crusted beard, that later appeared on the cover of National Geographic’s 125th anniversary issue. For years afterward, he continued to have a prolific mountaineering and photography career. Richards struggled with PTSD after the avalanche, and is now an advocate for mental health in outdoor athletes; he speaks candidly about being diagnosed with bipolar disorder as a teenager, as well as the trauma he experienced climbing.

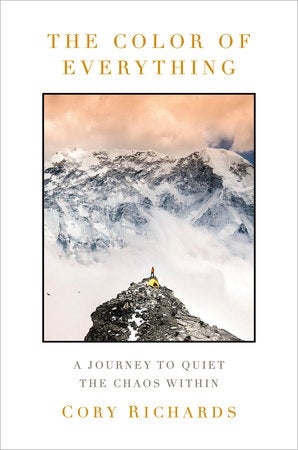

Below is an excerpt of Richards’s forthcoming memoir, The Color of Everything, out July 9, from Penguin Random House. The events in this chapter begin in the winter of 2016, following Richards’s divorce from his first wife and a months-long assignment for National Geographic in Angola, while he trains and climbs Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen.

The Color of Everything: A Journey to Quiet the Chaos Within

By Cory Richards

If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside. Learn more.

The TV is on, but I’m staring at a pair of fake eyelashes on the windowsill. I don’t remember where they came from but I see that they’ve been there long enough to collect dust. Divorce is confusing. In death there is finality. In divorce the living become ghosts and it’s easy to be haunted. Africa was brutal and illuminating. As difficult as the whole process was, I came home tired but hopeful and ready to move on, but moving on will take time.

There are days that I don’t leave the apartment and watch TED Talks between champion bouts of Family Guy reruns while looking at my phone and willing it to ring. Life isn’t bad, it just feels empty, like I’ve lost something and I don’t know what it is or where to look. It isn’t just the void of my marriage but something deeper and formless.

Depression is sneaky and sometimes we only really see its depths once we climb out. It’s hard to realize how deep you are when you’re transfixed by the crumbs on your belly. I also feel a strange sense of guilt for being depressed at all and at the same time it feels impossible to escape. People of all walks of life have experienced deep despair; some people just have to get up and work in spite of it in order to survive. I know it could be much worse and I feel more guilt that my legs just won’t move. Telling a depressed person they need to get out and be active is like telling an insomniac they just need to count some sheep and go to sleep. I look at the eyelashes again.

On a Tuesday the phone finally rings and Adrian Ballinger asks, “What are your plans this spring?”

I don’t even have plans for the rest of the day. “I don’t know,” I say. “Watch Family Guy?”

I’ve known Adrian for a decade. He’s handsome with dark features, light eyes, and freckled skin that’s seen too much sun. His ears are big and his cheeks seem stretched between his angular jaw and cheekbones. He’s relentlessly optimistic and laughs loudly and often and loves coffee. We like to call him “Stick,” which is short for “Stick Bug” because he’s tall and skinny, and I can vaguely see him on the other end of the phone when he says, “Do you think it’s time?” I know exactly what he is talking about but look at my watch anyway.

Four years ago, after far too much alcohol and too many hours awake, we’d made a plan. I’m listening to his British-Boston accent bending r’s into w’s and staring at myself in the mirror with the phone to my ear. He’s talking about climbing Everest without oxygen and I’m happy he can’t see the body I’m living in.

The toothpaste splatters block one eye and Adrian waits for an answer. Before fat Cory can say anything, athlete Cory hidden underneath speaks up and says, “Yes.” I pause. “But I’m, like, chubby and smoking a lot of cigarettes.”

“You have until April.”

The next morning I call my friend and mentor Steve House and ask if he’ll step in as my coach. He’s one of the best and most respected alpinists in the world, and if anybody can give me a shot at this in three months, it’s him. He agrees and I hang up the phone and then go to the gym and stay there for three months. I bike or walk up hills slowly, keeping my heart rate below 150 beats per minute while breathing through my nose. Steve says it will increase my aerobic capacity and mentions something about “fat adaptation.” I think I’m fat enough, but he explains that the term refers to teaching your body to use its fat stores by training fasted on long endurance days. At altitude it’s hard to eat, so it’s important that my body knows where to look for energy when I’ve run out of candy bars and burned through my love handles.

I’ve called myself a professional athlete for a decade but I finally understand what it means. There’s no glitz aside from crawling into my bed knowing that I trained as hard as I could. The only glamour is sleep. There is no time to smoke or drink or fuck. But because there is a light at the end of the tunnel, I’m more hopeful because I’m driven by purpose. A certain amount of loneliness is necessary in the service of an objective. It’s different from the vacuum of depression. I think if I’m going to be isolated either way, I might as well use it as a space to grow toward something.

Some days I’m embarrassed at how slow I have to walk to keep my heart rate low. When I do burpees, my torso jiggles, and I check the mirror every morning for bigger muscles and a smaller belly. Steve tells me to be patient, to train slow to go long, and reminds me, “It never gets easier, you just get faster.”

I wake up at 5 A.M. and pull on long wool socks and insulated running tights and stack on all my warm layers. I fill collapsible jugs with gallons of hot water for added weight in my backpack and scrape thick ice off my windshield without gloves. I listen to AC/DC and Rage Against the Machine while driving through the darkness to the trailhead. When it’s snowing, my headlights make the flakes fly past in streaks of white and it looks like I’m in Star Trek. On these days, the trail is empty and I see no one for hours. They are the same trails and the same day over and over and over.

When it’s too cold to train outside, I spend five or six hours on the treadmill with a backpack, reading King Leopold’s Ghost or The Looting Machine. Sometimes I watch Game of Thrones on my phone and fantasize about marrying Daenerys Targaryen. Who hasn’t? Anything to pass the time. Anything to keep my mind occupied. When I’m frustrated, Steve calmly reminds me that “it’s better to be consistent than talented” and I say, “I’d like to be both.” He laughs and replies, “Wouldn’t we all? Control what you can. Fuck the rest of it.”

My legs get faster. My heart rate goes down. I climb 9,000 feet on Monday and 11,000 on Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday.

After three months my muscles aren’t any bigger, just tighter, and I’m disappointed because I look nothing like the men and women I see on the cover of the magazines in the grocery store when I’m buying arugula. I sit on the floor and listen to my brittle tendons crunch as I roll them out and wonder why growth and improvement always hurt so much. The burpees start to feel less like torture and more like release and the crumbs on my slightly smaller belly are quinoa instead of chips. I’d kill a bunny for some chips.

By the time I get on a plane to Nepal in early April, my brain feels different. Everything seems brighter and the clouds of depression have parted around the summit in my head. I wonder if this is how a phoenix feels as I look at the shrinking flames around my feet and hope the lack of oxygen at the top of the world will starve the fire completely.

After ten days of acclimation, Adrian and I traverse the broken terrain of the Rongbuk Glacier and listen to ice crack and break as boulders crash down from the fresh glacial scar and the ground under my feet feels new. It’s broken and unsettled, toppling over itself and uncertain where it fits.

Two hours later we perch on the broad spine of a broken black slate and drink tea while we stare up at the mountain. I see exposed ice and small tendrils of snow swirling off a dark ridge. But the swirls aren’t small because the mountain is still five miles away and the ridge is 10,000 feet above us. We finish our drinks and Adrian drives us toward advanced base camp at 21,000 feet. He walks in long strides and tucks his thumbs in his shoulder straps as I struggle to keep up, questioning if I’m strong enough to do what we’ve come here to do.

After two days in advanced base camp, we start the pulse of acclimating, climbing high, sleeping low. Climbing higher, sleeping low. Sleeping higher. Climbing higher. It’s the rhythmic demystification of the Himalaya and the same method I’ve used on every high mountain. I remind myself that every climb feels impossible until you stand on top. So I memorize the steps and colors of the ropes and crevasses and always try to run under the big hanging ice cliff that guards the saddle of the North Col.

Ten days later, we sit in a hot tent at 23,031 feet and sweat. The interior can get to 75°F during the day and plummet to −20°F overnight. We drink Soylent, a supplement mix that tastes vaguely like pancake batter, while making Snapchat videos that fulfill our sponsorship commitments and tell the story of the climb in real time.

The idea to use Snapchat as a real-time storytelling tool came from Adrian’s girlfriend, legendary rock climber turned Himalayan star Emily Harrington. Now #EverestNoFilter is trending on the platform and hundreds of thousands of people are following the climb. Thousands of messages of encouragement, music recommendations, trolling, and the occasional picture of breasts flood our inbox. The connectivity of social media feels satiating and it also seems to blur and confuse motivation. But social media is ubiquitous now and at times it seems more important than the climbing itself. The premise of telling the story in real time is to offer an unfiltered and authentic look into what an expedition like this takes, but I quietly question how anything on social media can be authentic.

#HairByEverest begins to trend because my unwashed, sun-bleached hair makes me look homeless and Adrian’s looks like he’s just been electrocuted. People start posting pictures of their babies with wild hair and tagging it #HairByEverest and I like the playfulness of it all.

It’s May 24, 2016. I’m 36 years old. My alarm goes off at 12:30 A.M. but I’m already awake because “sleeping” at 27,224 feet is like “meditating” at a Metallica concert. Adrian’s headlamp comes on first and I shield my face for another minute of staring at the tent ceiling. It occurs to me that I spend a lot of time staring at different ceilings.

Eventually I sit up and start the stove, exhaling clouds that collide with the steam rising from the water. I wonder about matter changing form and how heat can make liquid levitate. Invisible currents make the vapors rise and swirl in the light of the headlamps. I look again at the ceiling and see all my breath from the sleepless night frozen in a sparkly frost. Gas becomes solid. I wonder if the altitude is getting to me and vacantly drag a finger in a line, watching the crystals fall onto my sleeping bag and melt.

I’ve been awake for 18 and a half hours, minus the 30 minutes when I managed to hang somewhere between sleep and wake, trying to forget about the sharp stone jabbing my left ass cheek. It will be five and a half more hours before the sun rises. I unzip the door just enough to see the thick stars of high places. My eyes trace along the uneven edges of the last 1,811 feet of Everest’s northeast ridge rising above me as a heavy black triangle.

I tuck back in and watch the steam in the tent and remember the past five months and the 36 years before that and everything that brought me to this place at this time as Adrian and Pasang and I prepare to leave for the summit. Pasang has joined the summit push for the sake of safety in numbers. Everything is done in silence. I no longer think about which boot or glove goes on first because I know it doesn’t matter. The only thing that can get me from here to there is my breath.

We leave the tent together and follow our familiar circles of light. The route climbs shallow snow to a steep series of wide granite cracks that lead toward the ridge. We check in with each other every half hour. Can you feel your fingers? Toes? Are you drinking? Eating? How does your head feel? Lungs? Are you slurring? Are you vomiting? What’s your name? Where are we?

Gradually the gap between Adrian and Pasang and me widens and I stop communicating by voice and start calling to them over the radio. After three and a half hours, the space between us has widened far enough that I feel alone and all my concern of not being fit enough has been swallowed up in the darkness. I’m not behind them, but ahead.

Adrian’s voice comes over the radio in slurs and tells me that he’s too cold and moving too slow to continue. He and Pasang are turning around.

“Are you sure?”

“Yes,” he says quietly.

“Do you want me to come with you?”

“No. Keep going.”

The communications are short and labored. But this was always the plan. If one of us couldn’t and the other was still strong, we’d separate. The team’s doctor, Monica Piris, who’s monitoring our climb from advance base camp, takes over the conversation. She’s spent many nights just like this, sleeping on the uneven floor of a dining tent curled up next to a tangle of cords and radios and solar batteries to keep it all going as her team plods through a dangerous and foolish darkness. It’s her job to keep us safe, to keep us moving, to keep us alive regardless of whether we’re climbing up or down.

I half hear her voice as I fumble with a rope. “Adrian, I need you to get back to the tents at high camp as quickly and safely as possible. When you’re there, please put on oxygen to get the blood flow back in your hands and feet and brain.” An indistinguishable mumble, half wind and half words, fills the air and I realize that Adrian is riding too close to the edge.

“Are you sure you don’t want me to come down?” Mumble. Monica answers instead. “Cory, how do you feel?”

“Good. My left pinky is tingling.”

“Keep fucking going! Adrian and Pasang will be safe. Go now. Go fast. I’ll talk to you in half an hour.”

The radio goes silent and I turn off my headlamp and sit. I listen to the breeze brushing across me and feel the wet collar of my down suit against my face. I am alone. I have no oxygen and no backup and no safety net other than my body and an honest accounting of myself. There are five other climbers somewhere on the route, but I can’t see or hear them. My life is apprehended in the confluence of breath and wind.

An hour later I approach the legs of a lifeless body hanging upside down in a tangle of rope. Tufts of loose feathers push through the torn suit, fluttering. I think of all the friends and people I’ve known who are no longer and lose count because my brain is too slow. I think of all the bodies I’ve seen on this climb and all the others in various states of decomposition and wonder again at matter changing form.

Sometimes they have faces. Sometimes they have mustaches and beards and eyelashes. Sometimes they’re hooded and hidden, as if they’re sleeping. Other times they have fingernails and their exposed flesh is yellow and black. Their skin is freeze-dried against bones that stick through, mummified after they took off their mittens in their final delirious moments. Their body and brain became confused and lied, telling them that they were warm and safe to shelter them from an opposite truth. Hormones and chemicals saturated their minds, creating a definitive hallucination to comfort them as they took their last breaths. This is the agreement you make with high mountains. Here the sliver of space that separates life and death is immediate, implicit, and yet totally incomprehensible.

My fingertips scream from cold as I unclip myself from the rope, reaching over the body and connecting myself to the line on the other side. I take a single step and walk further into life than the body behind ever made it.

When the sun finally rises, the summit pyramid is washed in fluorescent pastels and my pinky doesn’t tingle anymore. I take out my phone and try to film, annoyed at the intrusion. But the battery dies from the cold, and I’m relieved that the final steps will be just for me.

I don’t know how much time passes between this and the moment I sit down on the summit. An hour? Two? When I take the final step, there is nothing and no one and literally everything on earth is below me. I reach as high as I can and touch space. There is no place left to go. In some fundamental way, I’ve exhausted the search outside myself for anything that might make me whole. But I can’t see this now. For seven minutes I sit in silence and my awkward mind is literally the highest point on the planet.

After 40 hours without sleep I walk into advance base camp. The air feels thick and humid here. My heartbeat is slow and my mind is too tired to race, unable to comprehend the place I’ve been and how something so powerful can be so brief. I’m exhausted but restless and forget to go to bed. The world already knows what happened because, up until the final steps, they’d watched me. For his part, Adrian is as outwardly excited as everyone else but I can see how much he wanted it and how much it hurt to fail so publicly. I can see how much humility is required to let me shine. The depth of his character is revealed behind his skinny, chiseled face. He is more resilient than I ever could be.

A week later we’re in New York City and 2.3 million people are watching Adrian and me, with slightly gaunt eyes and sunburned faces, sit across from Gayle King on CBS This Morning. I wonder if the cameras can see the dry flakes of skin peeling from the tip of my nose. Later in the day, we sit across from Charlie Rose at his iconic wooden table and tell the story of the climb until he refocuses the conversation on what I’d disclosed about my mental health.

Just before the summit push, my anxiety peaked. I was overwhelmed by the climb, attention, and exhaustion. And, because there was no one else to talk to, I told a million people on Snapchat because that’s what the world does now. I’d matter-of-factly disclosed that I was bipolar and anxious and depressed and that everything was getting to me. I talked about being scared of the climb. Scared of failing. Scared of being scared and what that meant. Sending the videos into the world, I’d wondered if I was oversharing in the pursuit of attention. But even if I’d wanted to recant, it was too late. By morning my public persona had begun its transition into a spokesperson for mental health and the story behind the now infamous self-portrait from Gasherbrum II was slowly seeping out. Private became public. Superhuman became human. And, through the conceit of “no filter,” something mysterious became less so, inviting everyone into a much more real experience.

So when Charlie asks, I open up and speak candidly about the avalanche, PTSD, and bipolar because it seems natural. I can feel that it’s somehow important to break down the wall around me.

More interviews and TV follow. More press. More questions. More answers. When we finally unload a heap of tattered duffels on the curb at Newark Liberty International four days later, the expedition has generated over two billion media impressions.

I say goodbye to Adrian and Emily and walk to the gate, equally relieved and uncertain to be flying “home.” The world has shapeshifted again and I feel far away from the mountain, where things were less noisy, less frantic, more basic, and more meaningful. When the nice lady in a silk scarf with wings on her blue lapel leans over my seat and says, “Welcome home, Mr. Richards,” I wonder what she means because home is somewhere in a tent where the only planes are the ones that fly overhead and up there the captain is saying, “If you look out the window to your left, you can see Mt. Everest.”

After the divorce, the success of #EverestNoFilter is intoxicating. I float through days and weeks and am filled up when strangers thank me for speaking so candidly about my brain. While climbing Everest without oxygen is special (less than two percent of summits), it’s not new. It’s been done. For me, the accomplishment and celebration seem to be centered around something else. Suddenly my weaknesses are being celebrated as my strengths and I wonder if Achilles might have lived forever if he’d taken more care of his heel. And still I’m filling the inescapable space inside of me with the mountain itself because from it I can speak truths that I’ve held onto for too long.

I also know once the shine wears off, an emotional deflation will ensue and the comedown will be equal to the high. The next four years of my life will be devoted to trying to regain the same summit. I’ll stand there again, but it will never be the same.