At the Cyclocross World Championships earlier this month, Belgian cyclist Femke Van den Driessche had her bike confiscated by the UCI-the governing body of pro cycling-and a motor was found hidden in the seat tube of the frame. Believe it or not, hidden motors, or “mechanical doping,” has been on the UCI’s radar for some time, though this is the first time that a motor was actually discovered in competition.

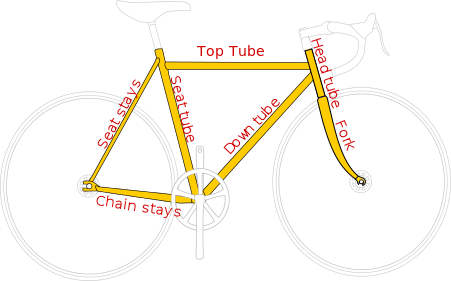

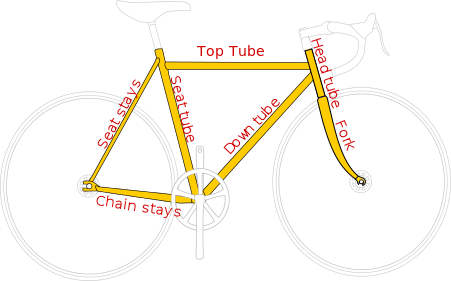

These motors are nifty if dubious little contraptions. The Vivax Assist is one of the most popular models, though the UCI has not specified what motor was found in Dressche’s bike. The 22-cm (8.7-inch), 750-gram motor is slotted into the top of a bike frame seat tube and pushed down to the bottom bracket. The motor kit comes with a gear ring that is positioned over the crankshaft and connects to the bottom of the motor.

The button to turn on this motor connects to an electronic control unit that is housed in a special seat post (provided with the motor kit) and routes to the motor via the seat tube. The standard kit comes with a battery bag that can be tucked under the saddle, though Vivax Assist offers an Invisible Performance Package that hides the battery and activation button in a water bottle to “invisibly transform your racing bike into an e-racing cycle” (see video below). The setup weighs between 1.8 and 2.2 kilograms (4 to 5 pounds), depending on battery options, but it provides an additional 100 to 150 watts of power to the driveshaft.

Ostensibly, motors like the Vivax Assist were created to give commuters a greater range and allow older or less proficient cyclists to ride with faster friends, and the Invisible Performance Package was developed to retain the aesthetics of your bike. But clearly the design has made its way into professional competition.

h/t Cycling Tips